OPEC US OIL, Airlines and Airports Planning for “Indefinite Uncertainty”

OPEC, U.S. Oil, Airlines and Airports share an interest in the impacts of OPEC’s decision to drop oil production. Two days ago, September 28, 2016, the 14 oil producing nations under the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) agreed to cut their collective oil output later this year in an effort to “bolster sagging oil prices” according to the New York Times. Even though the cut of up to 700,000 barrels a day would represent less than one percent of the total world production it sent global oil prices soaring by more than 5 percent.

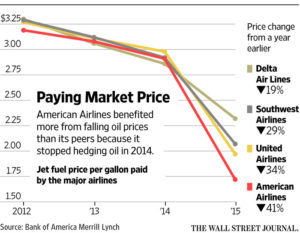

Just 6 months ago, March 20, 2016, the Wall Street Journal reported that “after  decades of spending billions of dollars to hedge against rising fuel costs, more airlines, including some of the world’s largest, are backing off after getting burned by low oil prices.” Fuel is the second largest expense after labor for many airlines. Oil prices peaked in 2008 at $147 a barrel hitting a low in February, 2016 of $26.21 a barrel. See also Reuters report on this topic.

decades of spending billions of dollars to hedge against rising fuel costs, more airlines, including some of the world’s largest, are backing off after getting burned by low oil prices.” Fuel is the second largest expense after labor for many airlines. Oil prices peaked in 2008 at $147 a barrel hitting a low in February, 2016 of $26.21 a barrel. See also Reuters report on this topic.

Oil markets have bounced back considerably since February 2016 to more than $40 a barrel but the global market remains substantially oversupplied. Conspiracy theories abound, however, regarding what nations are trying to hurt one another. Keeping the pendulum swinging creates uncertainty and makes it hard for airlines to devise sound fuel purchase strategies. The good news is U.S. oil producers were forced to get their costs under control with the new paradigm and are now profitable at levels just above $40 per barrel versus a requisite $60 a barrel. Presuming that this $20 cost reduction is maintained, that is a benefit to the airlines and the airports and communities they serve.

Why should communities and their airports care? When fuel prices are unpredictable airlines seek greater efficiencies and renegotiating labor contracts is not a cakewalk either. According to a 2012 report, airport charges are a sensitive subject during these uncertain times. See FlightGlobal, By Alex Thomas, London (2012). According to Thomas, New Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport proposed a 340% increase – an all-time high – in charges to all airlines based on high development costs of a new terminal and a troubled air carrier who owed large sums of money. New Delhi retracted their position following complaints by the International Air Transportation Association (IATA). IATA tracks fuel prices because of the sensitivities and impacts to airlines and the communities they serve.

Non-aeronautical revenues aside, airports have a socioeconomic interest to keep fuel prices down in most cases.[1] To this end, Airports have evolved into entrepreneurial enterprises to even out the uncertainty and to lessen cost impacts to airline rates and charges. The vulnerability of the airline industry, due to fuel prices, is largely out of their hands and involve world politics. Alex Thomas in his FlightGlobal report quoted Laurie Price, an aviation strategy consultant, who claimed that there is “a complete lack of appreciation of airline economics from airports and sometimes the other way [a]round.” ACI’s Rafael Echevarne, Director of Economics & Program Development at the time[2], noted that there is a realization “by governments around the world that airports are major engines of socioeconomic growth models for the territories they serve.”

Earlier this week I reported on the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) World Aviation Forum, international air service and economic development. In that article I pointed out a growing list of U.S. airports are hiring governmental affairs staff to bolster their war chests to compete for international routes. I would submit that communities would benefit to hire professionals who understand the dynamics of these complex issues. Jumping in the discussion on fuel prices should be added to their list of “things to do” sooner than later. The strength from main street joining in the discussion — to bolster the arguments in favor of evening out fuel prices — would be a win-win for the airlines and the communities they serve. See ICAO World Forum Article for further insights.

Earlier this week I reported on the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) World Aviation Forum, international air service and economic development. In that article I pointed out a growing list of U.S. airports are hiring governmental affairs staff to bolster their war chests to compete for international routes. I would submit that communities would benefit to hire professionals who understand the dynamics of these complex issues. Jumping in the discussion on fuel prices should be added to their list of “things to do” sooner than later. The strength from main street joining in the discussion — to bolster the arguments in favor of evening out fuel prices — would be a win-win for the airlines and the communities they serve. See ICAO World Forum Article for further insights.

[1]One example of when this is not true includes Colorado’s Aeronautical Board (CAB) supported by CDOT’s Aviation Division is funded by a fuel tax that was intended to support the states 74 public-use airports only 14 of which have scheduled air service. CAB’s funding was virtually cut off by the drop in fuel prices.

[2] Stefano Baronci currently serves in this capacity for ACI.